”This is the game that moves as you play”

From The Have Nots, by X

Phantasm: Digital Imaging and the Death of Photography (1994), After Photography (2009), Is Photography Over? (2010), New Photography (1985), Farewell Photography (2017), Photography 2.0 (2014), After Post-Photography (2016).

I’m sitting comfortably on my sofa while my PS3 loads its welcome screen, attempting to list in my mind all the most recent exhibitions, conferences and texts that have declared the medium of photography either defunct or reborn.

From Here On. PostPhotography in the Age of Internet and the Mobile Phone (2011), Bye Bye Photography (1972), Being: New Photography (2018), Photography After Photography (1996), Post-Photography: The Artist with a Camera (2014), The Post-Photographic Condition (2015), Augmented Photography (2017).

Like so-called ‘infinite death loops’ in video games – where a game is constantly loaded and its character instantly killed, stuck within a bug in the program – photography seems to have gotten trapped in a limbo, infinitely announcing its funeral and its reincarnation.

Is there really a bug somewhere in the program of photography? Is its phantom stuck in an infinite loop? As I take the PlayStation controller in my hands, I see the ghost. I see the specter of the photographic dispositif flickering on my monitor pixels – the buttons and levers of the camera apparatus have vanished, only to reappear as an on-screen interface and on the game controller.

I’m staring at licensed replicas of the Sony alpha series rotating seductively on my screen. Next I am zooming in on a simulated African elephant through a simulated viewfinder, attempting to take a good shot, hoping my client will be satisfied. I’m playing Afrika (Rhino Studios, 2008), where I wear the shoes of a young 24-year-old American photojournalist named Anna. Afrika is one of many game titles that simulate a camera interface and the act of photographic capture as their core game mechanics. It also attempts to gamify the formal qualities of my photographs, attributing points to the efforts of my in-game photo shooting.

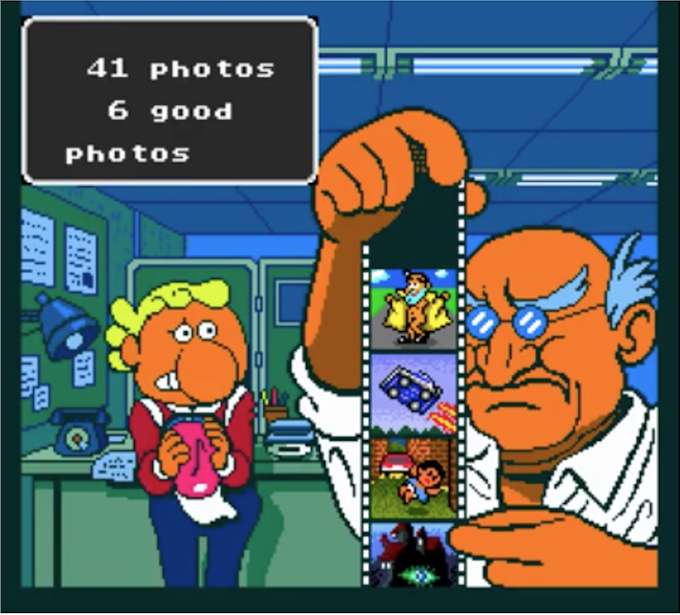

Just like in Pokemon Snap (HAL Laboratory, 1999) and Gekibo: Gekisha Boy (Tomcat System, 1992), the pictures I take in-game are evaluated and given a grade based on the algorithmic interpretation of my aesthetic choices. The dean of the school in Gekibo: Gekisha Boy looks at my negatives: “41 photos, 6 good photos. You used lots of film. You got assigned Photo! You pass! Good job!” Next I’m getting feedback from Prof. Oak about my pictures of Pokemons: “How’s the Size? 310 pts! Hmm… it’s so-so. How’s the Pose? 750 pts! Hmm… it’s so-so. How’s the Technique? OK! The Pokémon is right in the middle of the frame. I can double the score for you!”

Gamifying the decisive moment. Screenshot from “Gekibo - Gekisha Boy (PC Engine) - ¡Comentado! Análisis” published on YouTube by FranFrikiYT, published on 16 Jun 2014.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B5JEBHIS6oA

Gamifying the decisive moment. Screenshot from “Gekibo - Gekisha Boy (PC Engine) - ¡Comentado! Análisis” published on YouTube by FranFrikiYT, published on 16 Jun 2014.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B5JEBHIS6oA

Prof. Oak’s narrow and unimaginative idea of photographic aesthetics. Screenshot from “Pokémon Snap - Walkthrough Part 1 - [HD] (N64-Wii)” published on YouTube by Mrkerbster3, published on 24 Oct 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AfuMut5eaLc

Prof. Oak’s narrow and unimaginative idea of photographic aesthetics. Screenshot from “Pokémon Snap - Walkthrough Part 1 - [HD] (N64-Wii)” published on YouTube by Mrkerbster3, published on 24 Oct 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AfuMut5eaLcWhile the game mechanics and the dated graphics of these titles seem laughable, people who grew up with these media have often been influenced by them, with some even claiming that Pokemon Snap “taught [them] the basics of taking photographic evidence”1. Others have pointed out how such quantification of representations in games (through the standardization of what is to be considered a good photograph) promotes an oversimplified and unproblematic concept of photography2.

These are valid points and important reflections in a media landscape where games can influence the role of photography, but what about the ways photographic ideas affect games, and what happens when the boundaries between the two become blurry? In other words, I am not only looking at whether playing Afrika will make me a good wildlife photojournalist (although I have by now learnt that “no photo is worth risking life and limb over”, as I am told when waking after being attacked by a zebra while trying to get an incredible close-up shot), but rather at all the possible incarnations and transformations of photography in games, and also of games and as game.

Phew! Pearls of wisdom from Eric’s mansplaining. Screenshot from “Let's Play Afrika (PS3) Episode 14: Zebras are Scary...” published on YouTube by Robobin, published on 15 Oct 2016.

Phew! Pearls of wisdom from Eric’s mansplaining. Screenshot from “Let's Play Afrika (PS3) Episode 14: Zebras are Scary...” published on YouTube by Robobin, published on 15 Oct 2016.One could argue that photography has always been an “inherently gamelike practice” 3, although within video games a particular phenomenon called in-game photography has recently emerged. Adopted by a large number of players and artists, this term is a broad label that contains screenshot-ing practices within games, photo-mode functions, and photography simulations as well as modifications of game engines4. As an open call on Fotomuseum Winterthur’s online platform5 shows, there is a large and diverse community of both amateurs and professional photographers working with images in-game. A quick tour of online forums and sharing platforms also reveals the different interests and specific rules of in-game photography communities. Flickr abounds with groups like Landscape Photographers of In Game Worlds, a place where amateur in-game photographers share their images and comment. The group description is particularly fascinating, with its photographic language and its rules: “No ‘selfies’. No crotch shots. No dead animals. No shootings or killings. […] This is a place for landscape pictures only. They can be rural or urban.”6 Ethical discussions about manipulating images from games also vary, including communities – like the one around the forum of DeadEndThrills7 – where “Photoshop[p]ing a game screenshot is […] frowned upon.”8

Finally artists and photographers have started looking at this universe where photography and games appear to merge in unexpected ways, highlighting its ambiguity and exploring its new properties. Alan Butler9 and COLL.EO10 use in-game photography to reveal the hidden politics of representations in photorealistic simulations, while Roc Herms11 reenacts Ai Weiwei’s Study on Perspective within the world of Grand Theft Auto V (Rockstar Games, 2013). Kent Sheely12 modifies the game engine of DoD (Valve Corporation, 2003) to turn a First Person Shooter into a First Person War Photographer simulation and Claire Hentschker13 uses image-averaging algorithms to create romantic and sublime images out of appropriated gameplay videos from YouTube.

A Study of Perspective, © Roc Herms, 2015, courtesy of the artist

A Study of Perspective, © Roc Herms, 2015, courtesy of the artistAs the photograph merges with computationally created images, as photographers turn into players, and as cameras dissolve into PrintScreen buttons and simulated interfaces in-game, I wonder where the photographic ghost will take us next. On the other hand, wasn’t the photographic medium always a phantom to begin with? Drifting through different bodies and ideas, optical and algorithmic, geometrical and computational, static and moving? Photography remains always uncatchable and unrestrainable, and forever playing games.

1 Yotes Tony. 2013 “Gushing About: Pokemon Snap”, Weblog. Yote Games. 11 December 2013. http://www.yotesgames.com/2013/12/gushing-about-pokemon-snap.html

2 Orlando, Alexandra, and Betsy Brey. 2015. “Press A to Shoot”, Weblog. First Person Scholar. April 15. http://www.firstpersonscholar.com/press-a-to-shoot/

3 Poremba, Cindy. 2007. “Point and Shoot: Remediating Photography in Gamespace.” Games and Culture 2 (1): 53. doi:10.1177/1555412006295397.

4 For further reading about the different types of game-photography typologies see: Möring, Sebastian, and Marco de Mutiis, “Camera Ludica: Photography in Computer Games”, in Intermedia Games, edited by Michael Fuchs and Jeff Thoss. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

5 See Fotomuseum Winterthur’s SITUATION #6 In-Game Outsiders for the complete online collection of in-game photographic submissions: https://www.fotomuseum.ch/en/explore/situations/30482

6 Landscape Photographers of In Game Worlds (previously titled Landscape Photographers of Losa Santos and Blaine County, referring to the fictional setting of Grand Theft Auto V. The group creator recently decided to allow landscape photography images from all games) Flickr group: https://www.flickr.com/groups/landscapesoflossantos/rules/

7 Duncan Harris, a.k.a. DeadEndThrills is a professional screenshot artist working for game studios to create images used in advertisement and promotional materials. His site also contains a forum that became home to many in-game photography practitioners: http://www.deadendthrills.com/forum/

8 When asked about post-production and editing of images, in-game photographer K-Putt declares in an interview with Cnews.cz: “I remove little annoying things like one little blade of grass that looks through a shoe or something. I don't like to change the colors in Photoshop. That's what SweetFX is for. I want to capture the game like I see it ingame. Photoshoping a game screenshot is also frowned upon in our little screenshot community.“ Duncan Harris (aka DeadEndThrills) points out similarly: “I don't do any post work unless it's the very rare case of a glitch ruining a shot that's taken hours to set up. If a character's finger is clipping through something, for instance, then I'd probably fix that. Otherwise the shots are exactly as they're grabbed.“ A copy of the original interviews appeared on Cnews.cz is available here: https://www.pdf-archive.com/2017/11/23/appendix-to-article-screeshots-as-type-of-visual-art

9 Alan Butler’s Down and Out in Lost Santos (2015-) is a series of “virtual photographs“ documenting poverty in Grand Theft Auto V: http://www.alanbutler.info/down-and-out-in-los-santos-2016/

10 The artist duo made a homage and appropriation of Martin Parr’s Boring Postcards series with their Boring Postcards from Italy book, consisting entirely of images that make up the backgrounds of car-racing game Forza Horizon 2: https://concrete-press.com/boring-postcards-from-italy/

11 Roc Herms, Study of Perspective, 2015, http://www.rocherms.com/?project=study-of-perspective

12 Kent Sheely, DoD, 2009-2012, http://www.kentsheely.com/dod

13 Claire Hentschker, Avatar Above the Sea, 2017, http://www.clairesophie.com/gta-image-average-series/

by Marco De Mutiis